Similar Posts

The Hilarious Side of Scripture: Discovering the Funniest Bible Verse

Byadmin

In a world often filled with heavy conversations and serious topics, the Bible surprises us with its moments of humor, reminding us that laughter is a vital part of the human experience. Among its many teachings and stories, some verses stand out for their wit and playful wisdom, showcasing the lighter side of faith. Exploring…

John F. Kerry: A Legacy of Diplomacy and Leadership

Byadmin

In an era marked by pressing global challenges, John F. Kerry emerges as a pivotal figure in shaping international diplomacy and climate action. As the United States Special Presidential Envoy for Climate, Kerry leverages his extensive experience as a former Secretary of State to advocate for urgent environmental policies and foster collaboration among nations. His…

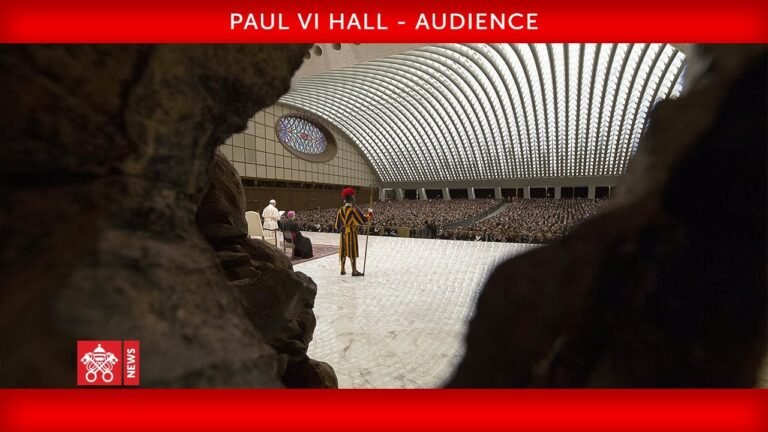

Exploring the Architectural Marvel of Paul VI Audience Hall

Byadmin

The Paul VI Audience Hall, an architectural marvel located within the Vatican City, serves as a significant venue for papal audiences and events. Designed by renowned architect Paolo Portoghesi, this modernist structure is characterized by its sweeping curves and striking interior, symbolizing the embrace of the Catholic Church towards the world. With a seating capacity…

Milwaukee Archdiocese priest on leave for alleged relationship with layman

Byadmin

(OSV News) — The Archdiocese of Milwaukee has put its judicial vicar, who was the pastor of two parishes, on administrative leave following media reports that surfaced indicating he has been cohabiting with a man in what appears to be a romantic relationship.

In a statement released on Dec. 1 to OSV News, the archdiocesan vicar for clergy announced that Father Mark Payne has been “put on administrative leave from his positions as Judicial Vicar and as pastor” of St. Monica Parish in Whitefish Bay and St. Eugene Parish in Fox Point, “effective immediately.”

Furthermore, Milwaukee Archbishop Jerome E. Listecki “is also commencing an official canonical inquiry into the matter,” stated Father Nathan Reesman, archdiocesan vicar for clergy, in the announcement.

The action follows a report from Nov. 30 in the Catholic media source The Pillar reported that Father Payne has been residing in a condominium with an unidentified layperson since 2003, whom he employed last year to instruct at St. Monica Parish School.

How Many Pages is 300 Words?

Byadmin

Are you wondering how many pages 300 words equate to? In this article, we will dive into the world of word counts and page lengths to give you a clear understanding of how much content you can expect from a 300-word piece. Whether you are a student working on an essay, a writer crafting a…

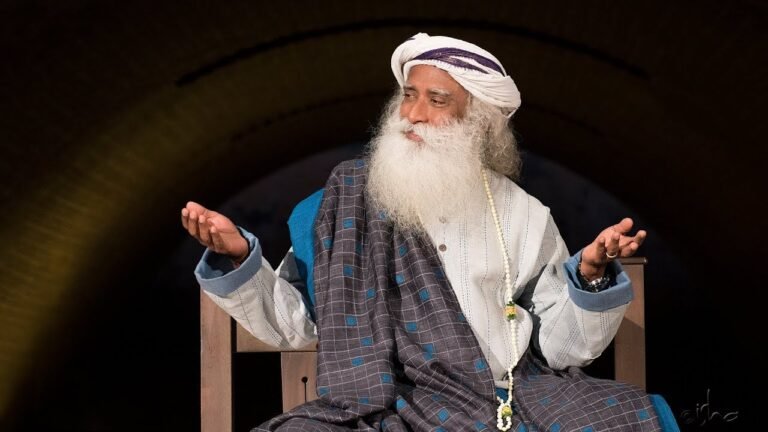

What Not to Do During a Solar Eclipse: A Hindu Perspective

Byadmin

As a celestial phenomenon that captivates millions, a solar eclipse brings with it a sense of wonder and excitement. However, for those observing this awe-inspiring event within the Hindu tradition, there are specific guidelines to follow to ensure spiritual well-being. Understanding what not to do during a solar eclipse is decisivo, as certain actions can…

What does it truly signify to pardon someone? This is among the most common inquiries my wife and I receive on our call-in radio show.

What does it truly signify to pardon someone? This is among the most common inquiries my wife and I receive on our call-in radio show.